The Social Media Deal Is Broken. It’s Time to Rewrite It.

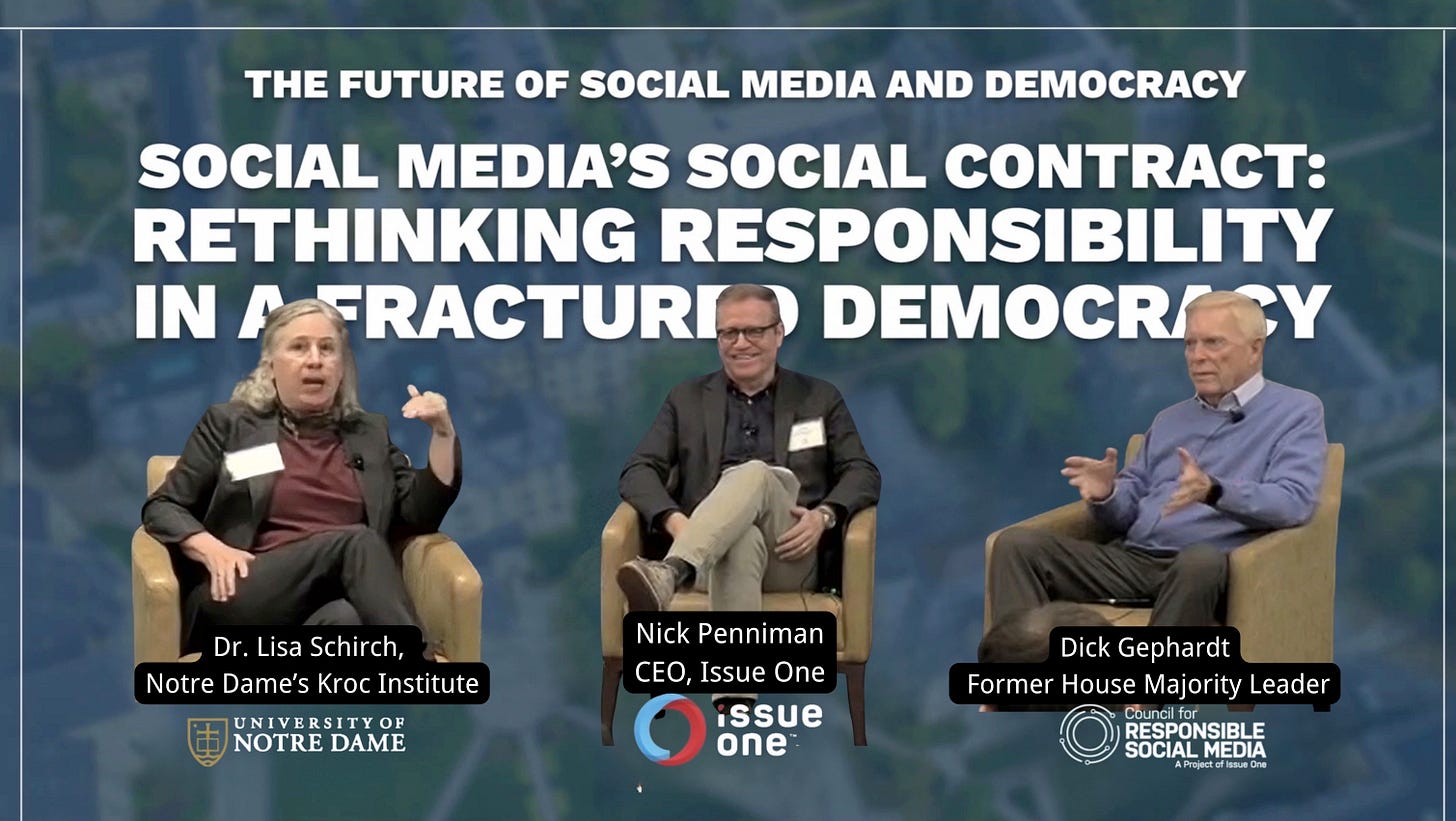

Social media was never meant to be a democracy killer. But if you watched today’s panel out of Notre Dame—“Social Media’s Social Contract: Rethinking Responsibility in a Fractured Democracy”—you saw something rare in this space: honesty.

Not posturing. Not “innovation theater.” Not half-hearted PR from platform reps who say the right things while doing the profitable ones.

No. Today was different.

Former House Majority Leader Dick Gephardt, Issue One CEO Nick Penniman, and peacebuilding scholar Dr. Lisa Schirch got up on stage and said, plainly, that the deal between tech platforms and the public is broken. Not frayed. Not strained. Broken. And if we don’t reimagine the terms—fast—we’re not just talking about mental health or polarization. We’re talking about the viability of self-government itself.

Gephardt, who spent nearly three decades in Congress and has had a front-row seat to the platform era, didn’t sugarcoat it. He described voting for Section 230—the legislative get-out-of-jail-free card that shields tech companies from liability for what happens on their platforms—as one of his great regrets. “We made them outside the legal system,” he said. “It was a horrible mistake.”

That line deserves to be etched into the national memory. Because when the people who helped build this mess are willing to say, out loud, that they got it wrong—it creates space for everyone else to stop pretending.

And pretending is what we’ve been doing for far too long.

We pretend the polarization is accidental. That the mental health crisis among teens is a tragic but unrelated outcome. That misinformation is just “bad content,” instead of the predictable byproduct of algorithmic systems engineered to amplify whatever drives engagement. Rage. Outrage. Conspiracy. Conflict.

Lisa Schirch didn’t let the moment pass. She’s spent years documenting the real-world consequences of this system—not just in the U.S., but across the Global South. In countries like Kenya, Jordan, Zimbabwe, and India, she found communities destabilized by social media platforms that exported the same high-friction, high-velocity engagement model that’s tearing the U.S. apart. The results were disturbingly familiar: local violence, frayed social trust, and rising authoritarianism.

Her point was clear: this isn’t just a design failure. It’s a moral one.

And it’s global.

Algorithms, she explained, aren’t neutral. They are choices—crafted, iterated, and optimized to serve the business models of the platforms that deploy them. These aren’t passive pipes. They’re amplifiers. Multipliers. And the design priority has never been truth, trust, or civic cohesion.

It’s attention. Always attention. Attention at any cost.

Penniman, who’s spent his career working to reform democracy and media, cut to the heart of the matter when he asked what happens when the people running these platforms—the ones who now shape the public sphere—are morally compromised. What happens when they’ve built systems that affect not just how we communicate, but what we believe, how we relate to each other, and whether we can even agree on a shared set of facts?

And let’s be clear: they are running our minds. Not in a sci-fi, mind-control sense, but in the most literal civic sense. They choose what rises and falls in your feed. What your kids see. What gets oxygen and what gets buried. If the people behind those levers are indifferent—or worse, driven purely by profit—we are not just in a content crisis. We are in a crisis of governance, of identity, of democracy.

Gephardt, to his credit, didn’t stop at regret. He pointed to the future. And he made it clear: regulation is part of the solution, but not the whole thing. We need alternatives. We need to stop treating social media as a utility we’re all stuck with and start building platforms that reflect public values. Project Liberty, one of the examples he cited, imagines that future. So do we, at the Sustainable Media Center.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Because the most profound thing about today wasn’t a plan or a policy. It was a tone shift.

It was three smart, experienced, politically diverse leaders saying: This is not sustainable. This is not accidental. And this cannot continue.

Gephardt spoke about knocking on doors in his district for 35 years. Literally. He went door-to-door for 12 hours a day, listening to constituents, facing their anger, engaging their views. They disagreed, he said—but they didn’t hate him. They didn’t hate each other. Now? That muscle of civic engagement has been replaced by a swipe, a like, a flame war.

“We’re going to lose this democracy,” he said, “unless we can pull this to a different place.”

I don’t think that’s hyperbole. I think it’s the clearest articulation of where we stand.

Young people are giving up on democracy. That’s not speculation. It’s measurable. They don’t trust institutions. They don’t see government as responsive. They’re being radicalized—not in some dark web fringe—but in mainstream digital spaces. TikTok, YouTube, Reddit, X. These are not just content platforms. They are identity factories. And they are increasingly indistinguishable from propaganda engines.

We built the internet to democratize knowledge. And it did. But in doing so, we also created a machine that now atomizes the truth, overwhelms our attention, and distorts our sense of the possible.

So no—this isn’t about content moderation policies or trust-and-safety teams or whether a post violates community guidelines. It’s about whether a functioning democracy can survive the business model that social media currently runs on.

Today, Notre Dame put that on the table. Not as an abstract question, but as an ethical imperative. And they did it with humility, precision, and urgency.

Now the rest of us need to catch up.

Because the platforms won’t fix this on their own. And they certainly won’t fix it fast enough.

It’s on us—policymakers, educators, technologists, designers, parents, and young people themselves—to demand a different digital world. One that’s designed not to extract value from our attention, but to support connection, context, learning, and civic participation.

The old contract is dead. Today we started talking, seriously, about what comes next.

Let’s not let this moment pass.